Knowledge Centre

The World as It Is and the Realities of Violence

Download full PDF report here.

1. Introduction

Violence is a concrete and persistent condition of life—historically enduring, socially embedded, and personally consequential. Despite living in what is regarded as the safest period in human history, individuals across the globe—and particularly within contemporary urban societies—continue to face an array of real and present threats to their physical safety, psychological well-being, and existential security. Yet for all its pervasiveness, interpersonal violence remains a subject that is frequently misunderstood, mischaracterized, or willfully ignored. It evokes feelings of discomfort, resists simplification, and defies the distance that abstraction affords.

This article serves as a critical foundation for understanding self-defense not merely as a physical skill, but as a morally and practically necessary response to the realities of violence. It does so by mapping the conceptual, relational, and empirical dimensions of interpersonal violence—offering a grounded framework that can guide risk recognition, ethical awareness, and defensive preparedness.

We begin by establishing a working definition of violence that is both precise and ethically functional. Drawing from the World Health Organization’s widely accepted formulation, we frame violence not simply as physical harm, but as the intentional imposition—or threat—of force that undermines bodily integrity, psychological stability, or developmental potential. This definition allows us to distinguish violence from related phenomena like conflict, aggression, or force, and serves as a conceptual lens through which we examine violence in practice.

From there, we explore the social contexts in which violence typically arises—family, peer relationships, public space, institutions, and identity-based targeting—each of which presents unique patterns of harm and vulnerability. While these environments may appear peripheral; they are where risk lives, often hidden beneath the surface of ordinary life.

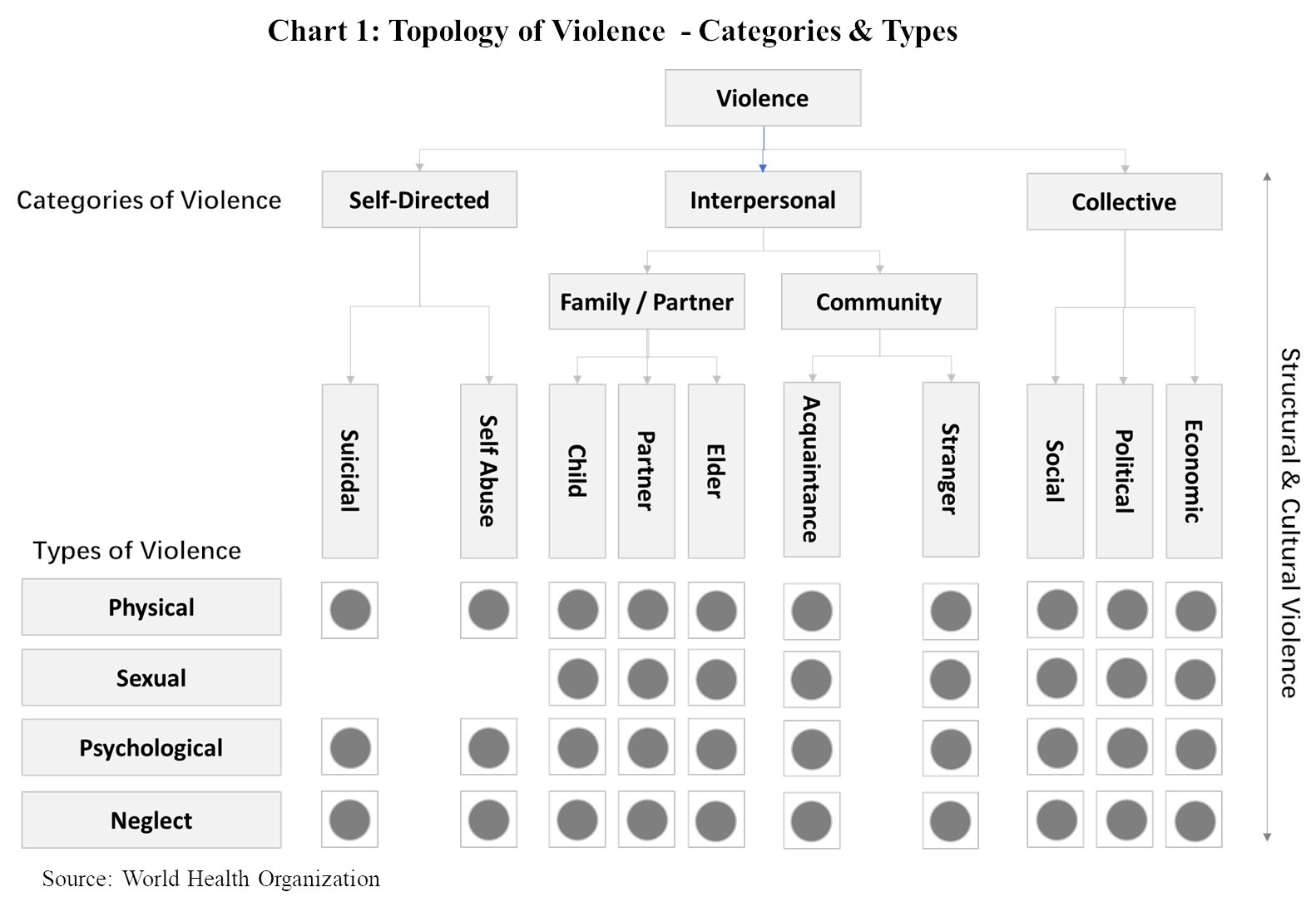

Next, we examine how violence is classified by the relationship between perpetrator and victim (self-directed, interpersonal, and collective), and by the nature of the harm inflicted (physical, sexual, psychological, or neglectful). These typologies are relationally simple but clarify the diverse ways that violence operates and the multiple forms it may take in a given encounter.

To deepen this understanding, we introduce supplementary classifications that distinguish between reactive and proactive violence, direct and indirect harm, and environmental conditions, including both structural and cultural, that shape the likelihood of victimization. These distinctions are especially vital in the context of self-defense, where tactical decisions must be made in seconds, and where ethical clarity must be maintained under pressure.

Finally, we ground this conceptual framework in empirical data. Drawing on national data from the United States—one of the most closely studied societies in terms of crime and public safety—we examine the scale and distribution of violent victimization across the population. We give particular attention to intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and child abuse, all of which highlight the personal nature of everyday harm. Although these may construed as marginal exceptions, they are in fact structurally recurrent, frequently unreported, and devastating in their impact.

Taken together, this article establishes that interpersonal violence is not rare, random, or easily dismissed. It is prevalent, patterned, and disproportionately borne by the vulnerable. Understanding its dynamics is a critical precondition for any serious discussion of self-defense.

In future anticipated articles, we will move from descriptive to evaluative. We will ask not only what violence is, but how and when one may respond to it justly. The right to self-defense, we will argue, is not merely permitted—but it is grounded in the conditions of moral agency itself.

But before one can act ethically under threat, one must first see clearly. This chapter is about learning to see.

2. What Is Violence?

2.1 Conceptual Definitions and Ethical Framing

Before we can ethically assess the risk of violence or respond to it through justified self-defense, we must begin with a clear operational definition of what violence is. Contrary to popular belief about personal intuition, emotion, or cultural assumption—it requires conceptual precision. Without such clarity, it becomes impossible to distinguish reasonable and legitimate threat from perceived offense, or protective action from excessive force.

A widely accepted and rigorous starting point is the definition provided by the World Health Organization (WHO): “Violence is the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation.”[i][ii]

This definition is significant for its breadth, depth, and applicability across fields such as public health, criminal justice, ethics, and interpersonal defense[iii]. It effectively extends the concept of violence well beyond immediate physical harm to include future long-term developmental disruption, psychological trauma, and material deprivation.[iv] It also does two crucial things: it emphasizes intentionality,[v][vi][vii] and it recognizes potentiality. Violence, in this framework, includes not only the execution of harm but also the credible threat of it.[viii]

Several important implications follow from this definition:

- Violence Is Not Limited to Physical Acts: The phrase “use of power” expands the scope of violence beyond physical force. It includes institutional, relational, or economic mechanisms of domination that intentionally coerce, intimidate, or harm.[ix] In this sense, violence may take the form of unjust detention, deprivation of care, economic marginalization, or the exploitation of vulnerability[x].

- Harm Is Multidimensional: Violence can result in more than just bodily injury although to be clear this is central. Additionally, it also encompasses psychological destabilization, disruption of cognitive or emotional development, social exclusion, and the denial of fundamental needs. Harm may be acute or chronic, visible or hidden, immediate or delayed.[xi][xii]

- Threat Is Also Violence: The threat of force—if credible and coercive—is itself also a form of violence. Threats can produce fear, loss of agency, and lasting psychological damage even if no physical act follows.[xiii] This is particularly relevant for ethical and tactical self-defense, where imminent threat may justify preemptive or protective action[xiv].

- Violence Can Be Immediate or Enduring: While violence is often understood as a direct and observable act—such as a physical assault—it can also unfold in enduring forms that cause harm over time. These may include long-term neglect, the intentional withholding of essential care, or the sustained use of coercion to control another person’s choices, movements, or opportunities.[xv]In such cases, the harm may not be confined to a single event, but instead, can results from repeated actions or omissions that predictably compromise a person’s well-being, safety, or ability to function. What unites both immediate and enduring forms of violence is the concept of deliberate intent[xvi]—the purposeful imposition or threat of harm that violates the conditions necessary for physical, psychological, or developmental integrity.[xvii]

- Violence Is Often Normalized or Misrecognized: Violence does not always appear as an extraordinary rupture. It may be routinized within domestic life, legitimated by cultural norms, or hidden behind the façade of bureaucratic policy.[xviii] Recognizing this is critical: violence is not only what shocks—it is also what erodes.

Understanding violence as intentional, multidimensional, and contextual is foundational to any meaningful response—whether ethical, legal, or tactical. It allows us to distinguish violence from related concepts such as conflict, force, or aggression. Not all force is violent (e.g., lawful restraint), and not all aggression leads to violence (e.g., hostile speech).[xix] Violence, as defined here, refers specifically to the intentional imposition or threat of harm that diminishes physical integrity, psychological well-being, or existential security.

In the chapters that follow, this conceptual framework will inform our approach to categorizing violence, analyzing its social and relational contexts, and identifying the specific risks to which persons—and their rights—are exposed. Only from such a foundation can ethical self-defense be responsibly developed.

2.2 Social Contexts of Violence

Violence does not occur in isolation. It arises within specific social contexts that shape its form, frequency, and impact.[xx] Understanding these contexts is essential for recognizing how violence is patterned in everyday life and how it influences personal safety, relational dynamics, and the need for defensive readiness.

This section outlines six major contexts in which interpersonal violence commonly occurs: family violence, peer violence, sexual violence, abuse of authority, public or community violence, and hate-motivated violence. Each context involves distinct relational dynamics, vulnerabilities, and consequences.

Family Violence

Family violence occurs within domestic relationships and may include child abuse, intimate partner violence (IPV), and elder abuse.[xxi] [xxii][xxiii] It often takes place in settings that are assumed to be safe, which can deepen its psychological impact. Victims may face emotional dependency, social isolation, or fear of retaliation, all of which can delay intervention or escape. Because family violence often occurs in private, it is frequently underreported and harder to detect.

Peer Violence

Peer violence arises among individuals of relatively equal social standing—such as classmates, colleagues, or neighbors—and includes bullying, harassment, physical altercations, or social intimidation.[xxiv] [xxv] It may be driven by rivalry, group pressures, status competition, or perceived insults. Peer violence can occur in schools, workplaces, or digital spaces,[xxvi] and it often exerts cumulative psychological harm, particularly when repeated or socially tolerated.[xxvii]

Sexual Violence

Sexual violence refers to any non-consensual sexual act, coercion, or unwanted contact.[xxviii] [xxix] [xxx] This includes assault, harassment, exploitation, and trafficking. Perpetrators may be strangers, acquaintances, or individuals in close personal or institutional relationships. The consequences for victims are often profound—spanning physical trauma, psychological distress, and long-term disruption of personal safety and trust.[xxxi] Sexual violence also frequently goes unreported due to stigma, fear, or emotional entanglement.[xxxii]

Abuse of Authority

Abuse of authority involves acts of harm or coercion committed by individuals in positions of trust or control—such as teachers, caregivers, supervisors, religious figures, or institutional agents. Victims are often those who rely on these individuals for care, guidance, or protection. Because the harm is enacted under the guise of responsibility or oversight, this form of violence is difficult to confront,[xxxiii] and its effects can be psychologically destabilizing.[xxxiv]

Community Violence

Community violence occurs in public spaces and typically involves individuals who may or may not know each other.[xxxv][xxxvi] Examples include physical assaults, robberies, or shootings. This form of violence contributes to public fear and environmental instability, particularly in areas facing economic hardship, weakened institutions, or social fragmentation.[xxxvii] Community violence is often cyclical, where previous victimization increases the likelihood of future harm.[xxxviii]

Hate-Motivated Violence

Hate-motivated violence is driven by hostility toward an individual’s perceived identity—such as their race, ethnicity, religion, gender, or orientation.[xxxix] [xl] These acts are often symbolic and retaliatory, intended to intimidate not only the victim but the broader group they represent. Hate-based violence inflicts psychological harm beyond the immediate target by reinforcing fear and exclusion within affected communities.[xli]

These contexts do not operate in silos. They often overlap, or reinforce one another—especially in environments where vulnerability is heightened by dependency, isolation, or limited access to protection.[xlii] Recognizing these contexts improves our ability to detect risk early, respond proportionally, and design defensive strategies grounded in practical awareness rather than abstract assumptions.

2.3 Topology of Violence: Perpetrator-Victim Relationship

Beyond the social settings in which violence occurs, it is essential to understand the relationships between those who inflict harm and those who suffer it. To this end, the World Health Organization (WHO) offers a widely recognized typology that classifies violence into three primary domains based on the identity of the perpetrator: self-directed, interpersonal, and collective violence.[xliii] This framework provides clarity on the structure of violent encounters and helps distinguish between different types of threats.

Self-Directed Violence

This category refers to harm that individuals inflict upon themselves. It includes self-injurious behaviors (such as cutting or burning), suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicide.[xliv] [xlv] Although not typically the focus of self-defense training, self-directed violence is relevant when considering the broader impact of trauma, chronic stress, or exposure to interpersonal abuse.[xlvi] It also reflects how violence may turn inward when external expression is suppressed or internalized.[xlvii]

Interpersonal Violence

Interpersonal violence is the most directly relevant category for self-defense.[xlviii][xlix] It encompasses violence committed by one individual against another and is subdivided into Family or Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), and Community Violence.

- Family or Intimate Partner Violence (IPV): Harm inflicted by individuals in close domestic or romantic relationships.[l][li] This includes spousal abuse, child maltreatment, and elder abuse.[lii] These acts often occur in private and involve recurring patterns of control or domination.[liii]

- Community Violence: Harm that occurs between unrelated individuals in public or social settings.[liv] Examples include assaults, muggings, and confrontations in streets, schools, or workplaces.[lv] Community violence often arises unpredictably and demands rapid recognition and tactical response.[lvi]

Collective Violence

Collective violence involves the use of force by larger groups—such as governments, armed organizations, or ideological factions—to achieve political, economic, or social objectives.[lvii] This includes warfare, terrorism, forced displacement, and targeted persecution.[lviii] While often beyond the control of individuals, collective violence sets the broader conditions in which interpersonal and community-level violence may emerge or escalate.[lix]

Understanding this typology is foundational for defensive awareness. It highlights that violence can arise in personal relationships, random encounters, or broader sociopolitical events—and each domain presents different challenges in perception, judgment, and response.[lx] Most critically, it reinforces that the primary concern of ethical self-defense is interpersonal violence: where the threat is direct, imminent, and personal.[lxi]

2.4 Forms of Violence by Type of Harm

In addition to classifying violence by the relationship between victim and perpetrator, it is essential to understand the specific nature of harm that violence inflicts. The World Health Organization identifies four primary types of violence based on how harm is expressed and experienced: physical, sexual, psychological, and neglect.[lxii] While these categories often overlap in practice, each represents a distinct form of violation—requiring different forms of recognition, intervention, and, in some cases, defense.

Physical Violence

Physical violence[lxiii] involves the use of force with a high likelihood of causing bodily harm, injury, disability, or death.[lxiv] Examples include hitting, choking, stabbing, burning, or the use of weapons. In the context of self-defense, this form of violence is the most visible and often the most immediately threatening—demanding rapid decision-making and tactical readiness. However, physical violence often leaves deeper psychological and social wounds than are visible on the surface.[lxv]

Sexual Violence

Sexual violence refers to any non-consensual sexual act or coercive sexual behavior.[lxvi] [lxvii] [lxviii] This includes rape, attempted rape, molestation, unwanted sexual contact, and sexual exploitation.[lxix] [lxx] [lxxi] Sexual violence may be inflicted by strangers, acquaintances, or individuals in positions of trust or authority. It is frequently used as a means of control or humiliation, and its long-term effects can be as much psychological as physical—leading to shame, isolation, and trauma that may persist for years.[lxxii]

Psychological Violence

Also referred to as emotional or mental abuse, psychological violence involves the use of verbal or non-verbal actions intended to inflict emotional pain, fear, humiliation, or manipulation. [lxxiii] [lxxiv] This includes threats, intimidation, isolation, surveillance, gaslighting, or deliberate undermining of self-worth. Though it leaves no physical marks, psychological violence can profoundly disrupt a person’s mental health and autonomy.[lxxv] Recognizing its signs—especially in domestic or institutional settings—is essential for both intervention and prevention.

Neglect

Neglect is the failure to meet the basic physical, emotional, or developmental needs of a dependent person—typically in a caregiving relationship.[lxxvi] [lxxvii] This includes withholding food, shelter, medical care, emotional support, or supervision.[lxxviii] [lxxix]Though it may appear passive, neglect can be deeply violent in its consequences—leading to malnutrition, psychological harm, developmental delays, or death.[lxxx] It is most commonly seen in cases involving children, the elderly, or individuals with disabilities.

These four forms of violence illustrate that harm is not limited to the physical. It can be imposed through touch or absence, action or inaction, presence or silence. For practitioners and students of self-defense, understanding the full spectrum of violence is essential—not all threats announce themselves through fists or weapons. Some unfold slowly, insidiously, and invisibly. But all have the potential to diminish autonomy, compromise safety, and demand a response.

2.5 Supplementary Classifications of Violence

While standard frameworks—such as the WHO typology—categorize violence by relationship (self-directed, interpersonal, collective) or nature of harm (physical, sexual, psychological, neglect), these classifications do not fully capture the motivational, temporal, and strategic dimensions of violent behavior.[lxxxi] For the purposes of self-defense, it is essential to develop a more detailed understanding of how violence is initiated, structured, and escalated across different contexts.

The following supplementary classifications provide a deeper conceptual toolkit for interpreting violence, especially in dynamic and high-stakes scenarios. To understand how violence escalates, it is important to distinguish it from related—but ethically and behaviorally distinct—phenomena such as conflict and aggression.[lxxxii] These classifications help clarify the spectrum from non-violent disagreement to coercive harm by differentiating reactive and proactive motivations, direct and indirect forms of expression, and the broader conditions that shape vulnerability. In doing so, they sharpen ethical awareness, threat recognition, and tactical preparedness.

2.5.1 Conflict

Not all oppositional behavior constitutes violence. At its most basic, conflict refers to a state of disagreement or incompatibility between individuals or groups—whether over goals, values, interests, or perceptions.[lxxxiii] Conflict may be internal (intrapersonal) or external (interpersonal or social), and it is a normal, even necessary, feature of human interaction.[lxxxiv] Crucially, conflict is not inherently harmful. It becomes ethically or tactically relevant when it escalates—through unmanaged tension, poor communication, or intent to dominate—into aggression or violence.[lxxxv] Understanding conflict as distinct from violence allows for more precise evaluation of risk and more proportional responses. Many conflicts can and should be addressed through dialogue, boundary-setting, or disengagement—long before they enter the domain of threat.[?]

2.5.2 Aggression

Aggression is a behavioral posture characterized by hostility, threat, or the intention to dominate.[lxxxvi] It includes actions—verbal, physical, or gestural—meant to provoke, intimidate, or coerce, even if no immediate violence occurs. In psychological terms, aggression functions as a precursor or correlate of violence, often revealing a readiness to escalate under specific conditions.[lxxxvii][lxxxviii]

Forms of aggression include:

- Verbal hostility: insults, threats, or inflammatory language;

- Non-verbal cues: clenched fists, narrowed gaze, aggressive stance;

- Spatial intrusion: deliberate encroachment into another’s personal space;

- Behavioral pressure: coercive posturing or controlling body language.[lxxxix]

Not all aggression leads to violence, and not all violence is preceded by visible aggression.[xc] However, early detection of aggressive cues is central to situational awareness and risk management.[xci] Recognizing aggression allows a potential victim to assess intent, manage distance, or engage in verbal or physical de-escalation. In the ecology of self-defense, aggression serves as a threat indicator—a signal that behavioral boundaries are being tested, and that protective measures may soon become necessary.

2.5.3 Force

While aggression signals potential intent, the enactment of harm depends on the application of force. Force refers narrowly to the direct physical exertion of one body upon another—pushing, pulling, striking, restraining, or otherwise imposing bodily contact.[xcii] It is immediate, concrete, and measurable, distinct from aggression (which may remain at the level of posture or threat) and from violence (which denotes harmful outcomes). In legal terms, “physical force” has been defined as any act exerted upon a person’s body to compel, control, constrain, or restrain movement, or any act reasonably likely to cause physical pain or injury.[xciii][xciv][xcv]

Not all uses of force are violent. A parent pulling a child out of traffic, a caregiver preventing self-injury, or a defender blocking a strike all involve physical force without necessarily producing harm. Violence emerges when force is disproportionate, excessive, or applied with the intent to injure.[xcvi] In this sense, force is best understood as the mechanism through which violence can occur, but not as violence in itself.

For self-defense, force represents the threshold of physical engagement—the point at which verbal management and spatial control give way to bodily contact. Crossing this threshold carries both risk and responsibility. Force can de-escalate a situation if applied in a controlled, minimal way, or it can escalate rapidly if applied without discipline. The disciplined use of force—no more and no less than necessary—ensures that defensive action remains proportionate, lawful, and ethically defensible, even under extreme pressure.[xcvii]

2.5.4 Reactive and Proactive Violence

Violence may be classified not only by form or relationship but also by motivational structure—that is, how and why it is initiated. A key distinction is between reactive and proactive violence.

Reactive violence is impulsive and emotionally driven. It typically arises in response to perceived provocation, threat, or frustration. This type of violence is marked by physiological arousal—heightened heart rate, tunnel vision, loss of fine motor control—and is often defensive, retaliatory, or panic-driven.[xcviii] Because of its volatility and intensity, reactive violence tends to escalate rapidly and can be highly unpredictable.[xcix]

Proactive violence, by contrast, is planned, deliberate, and instrumental. It is not driven by immediate emotional triggers, but by calculated goals—such as control, coercion, or personal gain. Examples include predatory assault, stalking, or ambush attacks.[c] Proactive violence may present little or no warning and is often carried out with a detached or unemotional demeanor.[ci]

Understanding this distinction is critical for self-defense. Reactive violence may allow for verbal de-escalation or tactical withdrawal, while proactive violence often demands immediate and decisive action, as the aggressor has already committed to a course of harm. Recognizing the difference can influence timing, strategy, and legal justification in a defensive encounter.

2.5.5 Direct and Indirect Violence

Violence also varies in how immediately and transparently it is delivered.

Direct violence is the most obvious form: it involves a clear perpetrator, a specific victim, and an act of harm that is observable in time and space.[cii] [ciii] [civ] Physical assaults, sexual attacks, and armed robberies fall into this category. Direct violence is the primary concern of most self-defense situations, as it constitutes an immediate threat to life, bodily integrity, or autonomy.

Indirect violence, on the other hand, unfolds across time or through intermediaries. It includes harm caused by neglect, abandonment, or the prolonged failure to meet someone’s basic needs.[cv] [cvi] [cvii] For instance, a caregiver who withholds medication from a dependent individual may not inflict visible injury, but the result may be life-threatening. Indirect violence is often harder to detect, harder to prosecute, and more likely to occur in closed environments of care, dependency, or institutional oversight.[cviii]

In both forms, the ethical response depends not only on the type of harm, but on the capacity to recognize and respond to it before it escalates into an emergency.

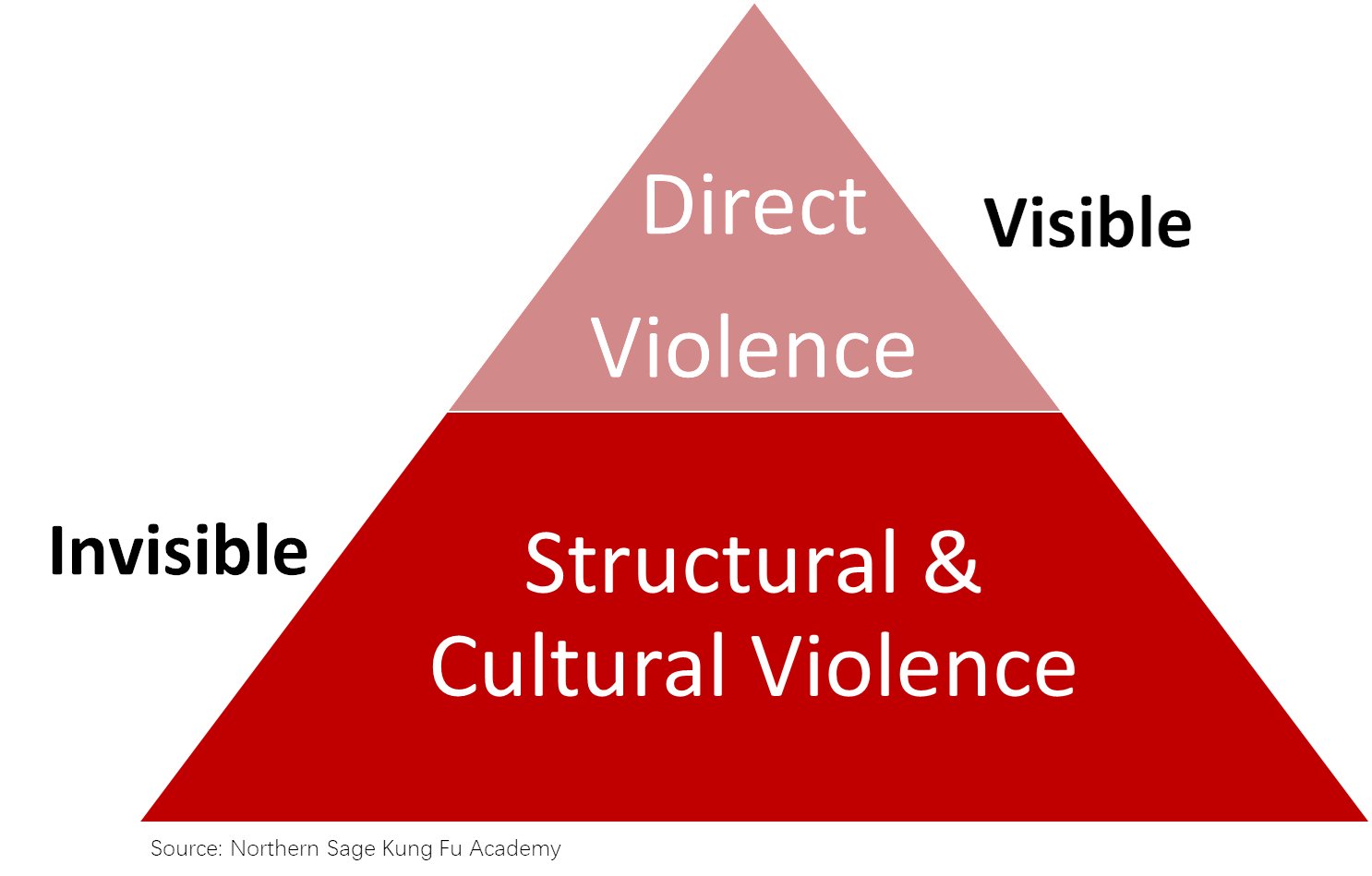

2.5.6 Structural and Cultural Conditions of Harm

While self-defense is primarily concerned with immediate threats, it is also shaped by broader conditions that influence exposure to violence. Two important classifications—structural and cultural violence—refer to environmental factors that increase the likelihood of harm, especially for vulnerable individuals and communities.[cix]

Structural violence refers to chronic conditions of deprivation or exclusion that can increase one’s exposure to interpersonal harm. These may include prolonged poverty, lack of access to healthcare, housing instability, or unsafe neighborhoods.[cx] Although not directly violence in the conventional sense, such conditions can create predictable patterns of vulnerability that shape who is more likely to suffer direct violence.[cxi] In this sense, structural violence is risk-amplifying rather than risk-neutral.

Cultural violence refers to the narratives, beliefs, or social norms that make certain forms of harm more likely to occur or be tolerated.[cxii] Examples include belief systems that normalize domination in relationships, devalue certain populations, or discourage reporting of abuse.[cxiii] To be clear, cultural violence does not directly inflict harm, but it conditions the environment in which harm becomes more acceptable, invisible, or difficult to challenge.

Though neither form is necessarily actionable in a self-defense encounter, both contribute to the ecology of violence and should inform how risk is assessed, how communities are protected, and how ethical awareness is cultivated.[cxiv] [cxv]

Understanding violence requires more than recognizing visible acts of force. It requires the capacity to distinguish between intent, method, timing, and context. These supplementary classifications provide a richer lens through which to interpret real-world threats. They also help practitioners of self-defense avoid simplistic or reactive responses and instead cultivate a form of protective awareness that is precise, proportional, and ethically grounded.

3. CASE STUDY ON VIOLENT VICTIMIZATIONS IN THE UNITED STATES

3.1 Contemporary Realities: Violence and Property Crime in 2023

To understand the practical urgency of self-defense, one must begin with a sober appraisal of the prevalence and scale of violence in contemporary society. Violence is not a distant or infrequent aberration—it is a persistent feature of ordinary life. In the United States, one of the most statistically monitored societies in the world, data from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) offer a striking portrait of just how widespread and entrenched interpersonal violence has become.[cxvi]

Administered annually by the U.S. Census Bureau on behalf of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the NCVS is the nation’s most comprehensive survey of crime victimization. Unlike police reports, which capture only offenses known to law enforcement, the NCVS estimates both reported and unreported crimes through large-scale, household-based interviews. This allows it to uncover the “dark figure” of crime—particularly in areas like domestic violence, sexual assault, and simple assault—where non-disclosure and institutional mistrust remain high.[cxvii][cxviii]

While its strengths lie in breadth, consistency, and the inclusion of contextual details—such as offender relationships, location, and victim response—the NCVS also has limitations. It excludes fatal crimes like homicide, excludes individuals under 12 or those in institutional or unstable housing situations, and relies on self-reporting, which can be compromised by fear, stigma, or memory gaps.[cxix] Nonetheless, it remains one of the most reliable instruments for capturing the actual experience of violence in American life. The data presented in this section draw heavily from the NCVS, not merely as a statistical repository, but as a window into the lived ecology of risk that self-defense must contend with.

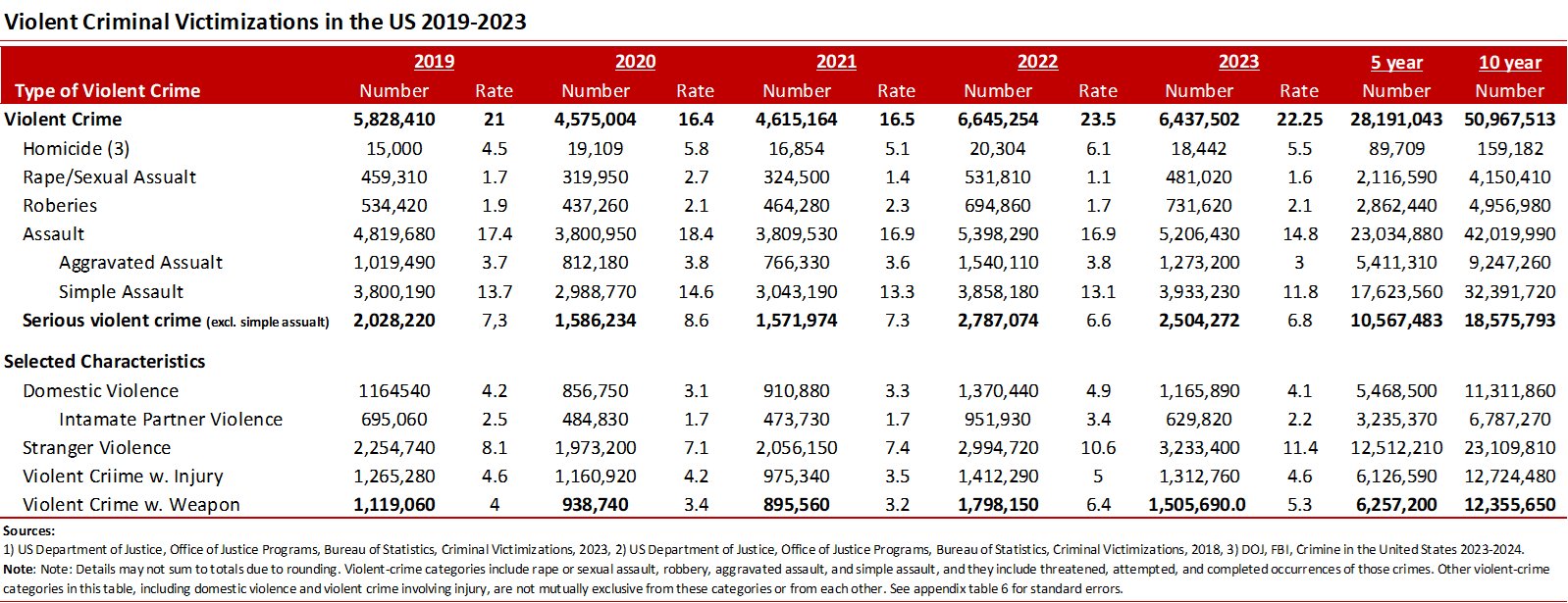

In 2023, Americans experienced an estimated 6,437,502 violent victimizations, representing a rate of 22.25 incidents per 1,000 persons aged 12 or older.[cxx] This includes approximately 18,442 homicides,[cxxi] 481,020 rapes or sexual assaults, of which 1.27 million were aggravated. Notably, 2.5 million cases—or roughly 39%—qualified as serious violent crime (excluding simple assault), and more than 1.3 million involved injury to the victim. Weapons were used in 1.5 million incidents,[cxxii] and firearms were present in over 23% of cases.[cxxiii]

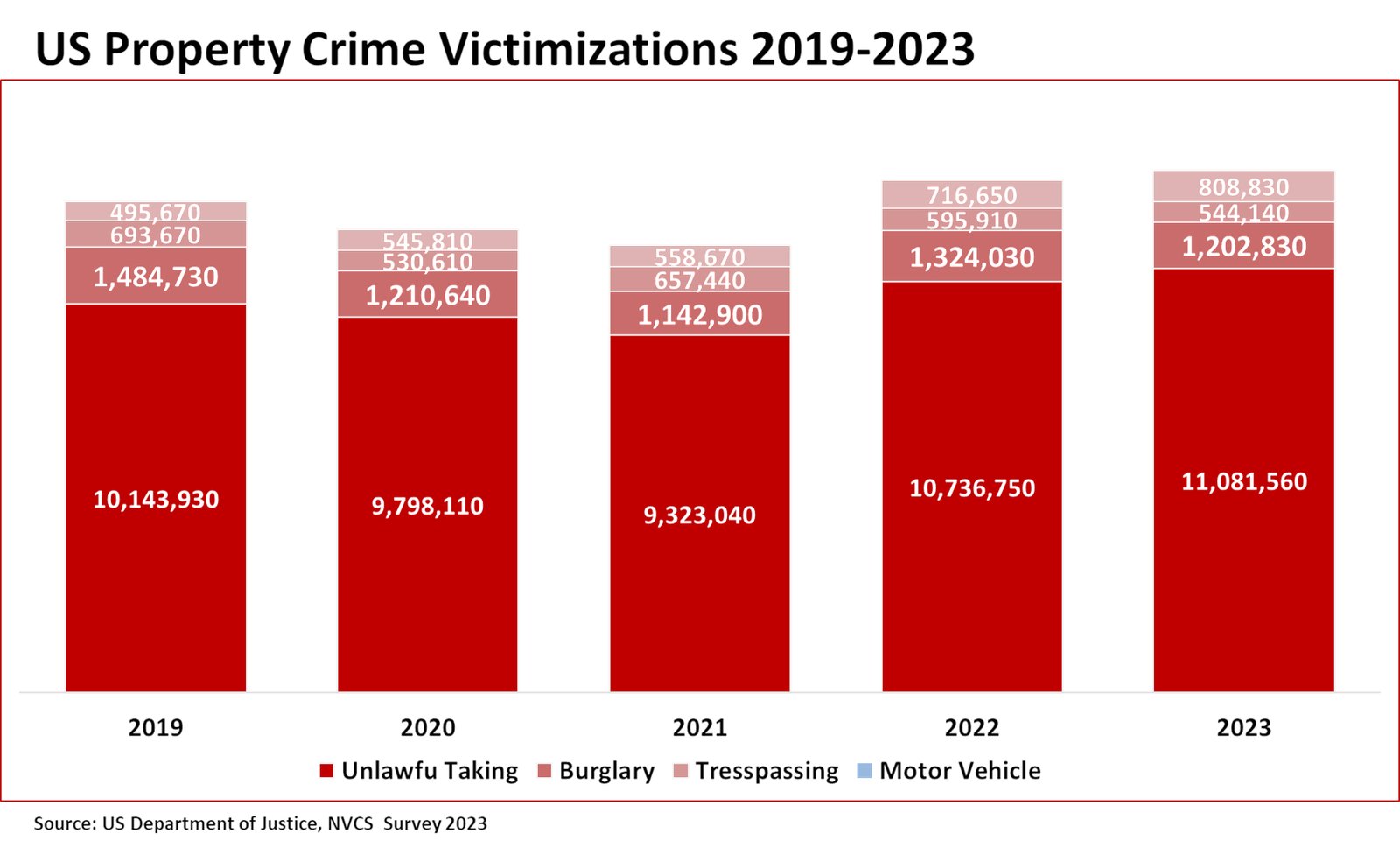

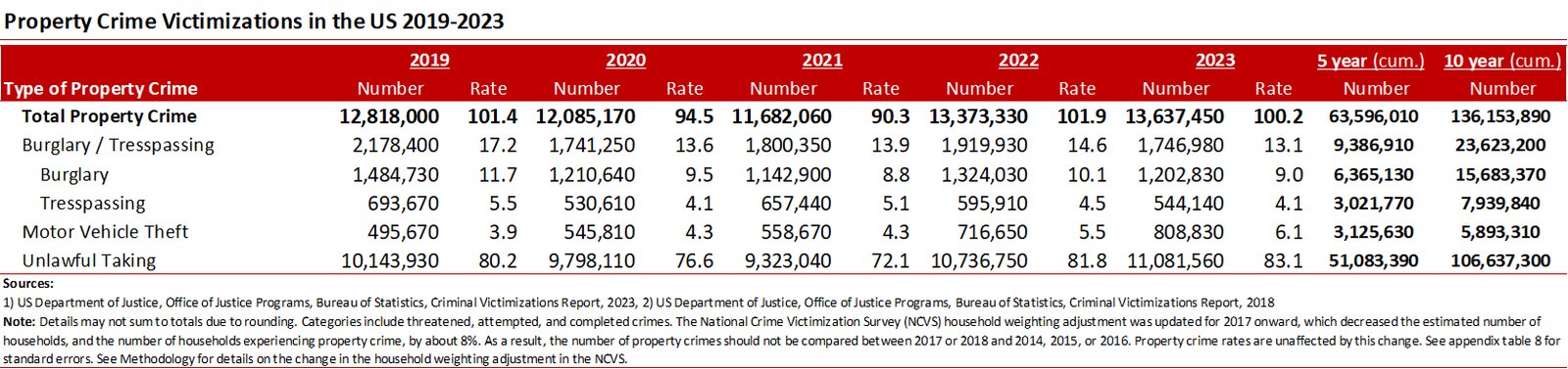

Property crime remains even more prevalent. In 2023, the NCVS recorded 13,637,450 property crime victimizations,[cxxiv] including 1.2 million burglaries, 544,140 trespassing incidents, and an alarming 808,830 motor vehicle thefts—the highest such figure in a decade.[cxxv] The overall rate of property crime stood at 100.2 per 1,000 households, with unlawful taking/theft accounting for more than 11 million incidents.

These figures underscore a critical truth: violence and violation are not abstract phenomena. They are measurable, patterned, and embedded in the ordinary fabric of life. Understanding their scope is not merely statistical—it is ethical and strategic, providing the empirical backdrop against which self-defense must be both practiced and justified.

3.2 Five-Year Trend Analysis: 2019–2023

Over a five-year span, national crime data reveal a landscape that is both volatile and instructive. From 2019 to 2023, the number of violent criminal victimizations rose from 5.8 million to 6.4 million,[cxxvi] [cxxvii]while serious violent crimes increased from 2 million to over 2.5 million. Although the rate of violent crime declined in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, it surged again in 2022 and 2023, marking a steady 23% increase in overall violent crime and a remarkable 45% increase in serious violent offenses from their 2020 lows.

In terms of victimization characteristics, five-year cumulative figures show over 5.4 million cases of domestic violence, including more than 3.2 million incidents of intimate partner violence.[cxxviii] Stranger-perpetrated violence accounted for an estimated 12.5 million cases, and 6.1 million violent crimes involved injury.[cxxix] Most concerning is the sharp rise in violent crimes involving weapons, which totaled 6.25 million from 2019 to 2023.[cxxx]

Property crime trends during this period are equally revealing. Total property crimes rose from 12.8 million in 2019 to 13.6 million in 2023, with motor vehicle thefts climbing from 495,670 to over 808,000—a staggering 63% increase.[cxxxi][cxxxii] In total, the U.S. saw more than 63.5 million property crimes over five years, with burglary and trespassing accounting for over 9.3 million and unlawful taking/theft representing 80% of the total.

3.3 Patterns and Implications

Three empirically observable patterns emerge from the five-year data on violent and property crime in the United States.

First, the absolute volume and rate of both violent and property crime remain consistently high, with noticeable surges in specific years. Violent crime rose from 4.6 million incidents in 2021 to over 6.4 million in 2023,[cxxxiii][cxxxiv] with the rate increasing from 16.5 to 22.25 per 1,000 persons. Assaults—especially simple assaults—make up the bulk of this increase, accounting for nearly 5.2 million incidents in 2023 alone. Meanwhile, serious violent crimes (excluding simple assault) also rose sharply, from 1.57 million in 2021 to 2.5 million in 2023,[cxxxv] [cxxxvi]indicating not just a rise in frequency but in the severity of interpersonal harm.

Second, property crime levels have likewise rebounded in recent years. After a low point in 2021, both the number and rate of property crimes rose steadily through 2022 and 2023, culminating in 13.6 million incidents last year. Motor vehicle theft shows the most dramatic increase, rising from 558,670 incidents in 2021 to over 808,000 in 2023—a 45% jump in just two years.[cxxxvii] These data suggest a shift in criminal tactics toward high-value, high-mobility targets and point to vulnerabilities in both urban infrastructure and personal asset security.

Third, weapon involvement and injury rates in violent crimes have intensified. In 2023, violent crimes involving a weapon reached over 1.5 million cases, while violent incidents resulting in injury exceeded 1.3 million.[cxxxviii] These figures reflect a sustained increase from 2021 levels, indicating that not only are more violent crimes occurring, but more

of them are physically injurious and potentially life-threatening. This escalation in tactical risk underscores the ethical and practical necessity of being prepared for encounters that involve immediate threats to life and bodily integrity.

Taken together, these patterns challenge any complacent narrative that interpersonal violence is in long-term decline. While national crime rates remain lower than their historic peaks in the early 1990s, the past five years show renewed volatility—particularly in categories relevant to personal safety. Interpersonal violence in the United States is not an occasional crisis—it is a persistent reality. It is neither confined to the marginalized nor exclusive to urban spaces. It occurs in homes, schools, workplaces, and on the street. It often unfolds without warning and disproportionately affects those who are unprepared, under-protected, or underserved by institutional safeguards.

This is the empirical backdrop against which the ethics and practice of self-defense must be understood. The decision to prepare for violence is not rooted in paranoia—it is anchored in fact. These statistics are not abstract—they are a call to moral and practical readiness. In a world where violence remains statistically certain, the right to self-defense becomes not merely rational, but indispensable.

3.4 Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Assault

Among all forms of interpersonal harm, intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual assault are among the most widespread, complex, and personally devastating. They occur not in remote or anonymous spaces, but within homes, bedrooms, relationships, and caregiving contexts—where trust and vulnerability are most concentrated. These forms of violence are particularly insidious because they often unfold over time, under conditions of emotional dependency, secrecy, and psychological manipulation.

In 2023 alone, the National Crime Victimization Survey recorded 1,165,890 incidents of domestic violence in the United States—approximately 4.1 incidents per 1,000 persons.[cxxxix] Of these, 629,880 were attributed to current or former intimate partners, reflecting a rate of 2.2 per 1,000.[cxl] Rape and sexual assault victimizations totaled 481,020, underscoring the continued prevalence of sexual violence in both public and private life.[cxli] While this figure represents a modest decline from the 2022 peak, it remains elevated compared to pre-pandemic lows—suggesting that such harm is not episodic but enduring.[cxlii]

Over the five-year period from 2019 to 2023, nearly 5.47 million domestic violence incidents were reported nationally, with 3.24 million involving intimate partners. Rape and sexual assault cases exceeded 2.1 million.[cxliii] These are not isolated events; they reflect a persistent pattern of violence embedded in relational life—where the lines between affection, obligation, and control blur dangerously and in damaging ways.

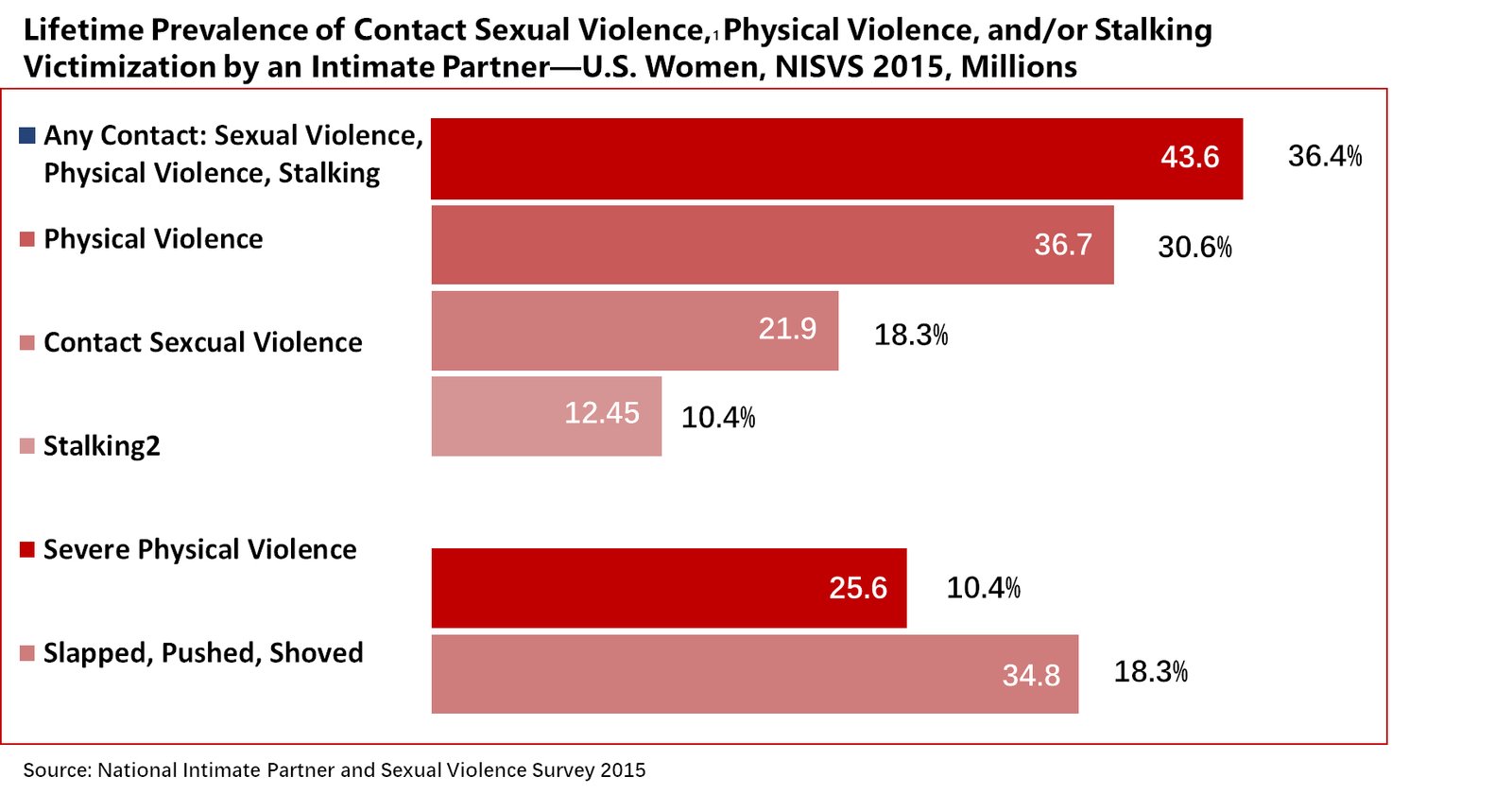

Survey data from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey 2016/17 (NISVS) further contextualize these findings. Nearly one in two women (47.3%) in the United States—approximately 59 million—reported experiencing contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime.[cxliv] In the 12 months preceding the survey, 7.3% of women (9 million) experienced such violence, underscoring that this is not merely a historical condition, but a recurrent reality.[cxlv]

The report further indicates that 41.0% of women (51.2 million) who experienced IPV also endured IPV-related impacts—including physical injury, post-traumatic stress, chronic fear, and disruptions to work, school, or access to legal and medical services.[cxlvi] These consequences illustrate that violence does not end with the moment of harm. It reshapes the landscape of a person’s daily life—disrupting relationships, impairing autonomy, and compromising the very conditions under which agency is exercised.

Sexual violence within intimate relationships is especially alarming. The NISVS reports that nearly one in five women have experienced some form of sexual violation by a partner—whether through coercion, forced intercourse, or unwanted contact.[cxlvii] These are not rare exceptions. They are systemic expressions of control in which consent is steadily eroded and replaced by domination.

But physical violence is even more widespread—and no less patterned. Forty-two percent of women (52.4 million) reported experiencing physical violence by an intimate partner. Nearly 39% were slapped, pushed, or shoved; and 32.5% (40.5 million) endured severe forms of assault, including being choked, beaten, burned, or attacked with weapons.[cxlviii] These numbers confirm what survivors and advocates have long understood: IPV is not an occasional loss of temper. It is an instrument of control, degradation, and fear.

Beyond physical acts, psychological aggression and coercive control are equally pervasive. Nearly half of all women (49.4%) have experienced psychological aggression, and 46.2% (57.6 million) were subjected to controlling behaviors—such as surveillance, isolation, threats of self-harm by the abuser, or financial restriction.[cxlix] These forms of violence leave no visible injuries, but they corrode dignity, erode autonomy, and create an atmosphere of chronic fear and compliance.

And yet, even these numbers likely fall short of the full picture. IPV and sexual violence remain among the most underreported crimes in the country—constrained by fear, stigma, financial dependence, or emotional entanglement. This silence not only conceals harm; it perpetuates it. The failure to report is not just a private act of fear—it reflects gaps in support, protection, and justice.[cl]

Understanding the magnitude and persistence of IPV and sexual assault is not simply an academic or legal task—it is a prerequisite for ethical and practical readiness. These forms of violence demand not just recognition, but vigilance. They are not marginal—they are central to the ecology of harm in contemporary life.

3.4.1 Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence

The consequences of intimate violence extend far beyond the moment of physical harm. Physically, survivors often endure chronic pain, gynecological complications, and injuries ranging from bruises and fractures to life-threatening trauma.[cli] IPV is closely linked to reproductive harm, including sexual dysfunction, miscarriage, infertility, and increased risk of sexually transmitted infections.[clii]

Psychologically, the toll can be enduring. Many survivors suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, disordered eating, substance misuse, and sleep disturbance.[cliii] These harms are often compounded by emotional degradation, coercive control, and the isolation that abusive relationships cultivate. At its most extreme, intimate violence results in homicide, suicide, and maternal death—transforming chronic abuse into fatal outcomes.[cliv]

These impacts are not distributed evenly. Women, particularly those from marginalized communities, experience higher rates of IPV and sexual violence.[clv] But all individuals—regardless of gender, background, or orientation—are at risk. The hidden nature of this violence makes it particularly difficult to prevent or confront. It is not merely a private problem; it is a public crisis with moral, legal, and existential consequences.

While IPV disproportionately affects women, men also experience significant levels of harm. According to the 2016/2017 NISVS, more than 44% of men (52.1 million) in the United States reported experiencing contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime, and 6.8% (8 million) reported such violence in the 12 months preceding the survey.[clvi] Over 31 million men also reported suffering IPV-related impacts such as fear, injury, or disrupted daily functioning. Notably, 42.3% of men experienced physical violence, with nearly 25% reporting severe assaults. In addition, 45.1% of men experienced

psychological aggression by a partner, and 42.8% reported forms of coercive control—including monitoring, destruction of property, and restrictions on autonomy.[clvii] These findings highlight that while patterns and contexts may differ, intimate violence is not exclusive to one gender. It is a widespread and relationally embedded form of harm that requires inclusive recognition and response.

In the context of self-defense, intimate partner violence poses unique challenges. It often unfolds in private spaces where intervention is delayed or unavailable. It involves perpetrators with whom victims share emotional, financial, or familial ties. And it is marked not just by physical threat, but by persistent erosion of autonomy and selfhood. Recognizing IPV as a central domain of risk demands that our concept of defensive readiness be expanded—not just to confront strangers on the street, but to confront harm where it is most often suffered: within the intimate fabric of ordinary life.

3.5 Child Abuse and Violence

3.5.1 Maltreatment and Fatal Harm

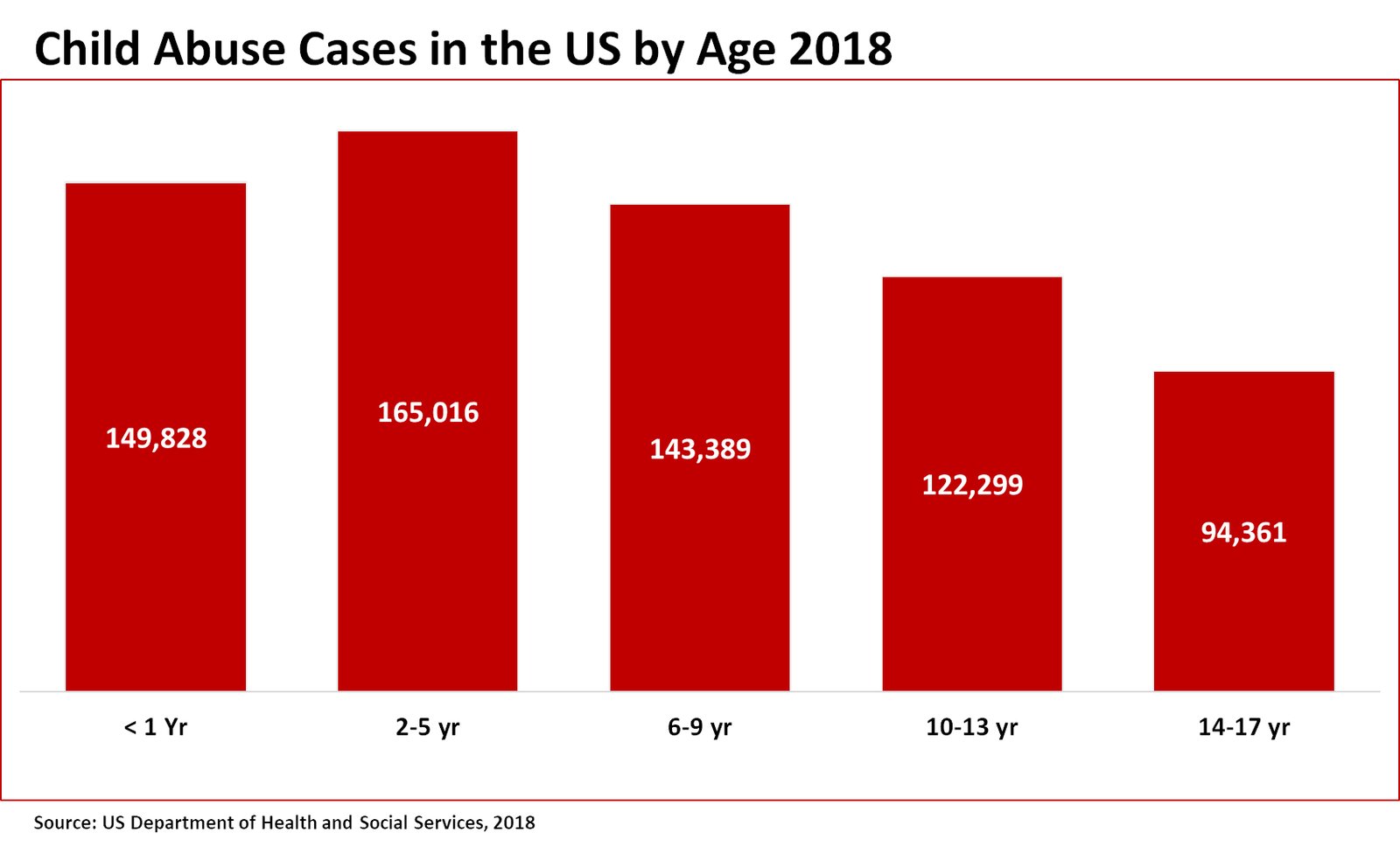

Among the most urgent and harrowing forms of interpersonal violence is harm inflicted upon children—those least capable of self-protection and most reliant on the care of others. Child maltreatment encompasses a range of violations, including physical assault, sexual abuse, emotional degradation, and chronic neglect. At its most extreme, this violence becomes fatal. In 2023, an estimated 2,000 children died as a result of abuse or neglect in the United States—making child maltreatment not only a profound developmental and moral crisis, but one with irreversible consequences.[clviii]

Fatalities from maltreatment are not evenly distributed across childhood. They concentrate overwhelmingly at the youngest end of life. Children under the age of one accounted for nearly half of all child deaths, with a fatality rate exceeding 24 deaths per 100,000 infants—the highest of any age group by a wide margin.[clix] Nearly two-thirds of all fatalities occurred among children under the age of three.[clx] These are not abstract figures. They reflect a stark truth: the closer a child is to total dependency, the greater their risk of invisible suffering, delayed detection, and, in some cases, death.

Such outcomes rarely occur in isolation or surprise. They are often preceded by earlier harm—missed signals, ignored warnings, and systemic failures in oversight or support. For every child who dies, many more endure abuse that is chronic, hidden, or insufficiently addressed. In 2023, over 546,000 children were confirmed victims of maltreatment—a national rate of 7.4 victims per 1,000 children.[clxi] Given widespread underreporting and definitional variability across jurisdictions, the true number is likely much higher.[clxii] The challenge of measurement is not unique to the United States: UNICEF has documented similar global difficulties in capturing the full extent of violence against children, noting significant variation in data collection, definitions, and reporting mechanisms.[clxiii]

What these data make clear is that violence against children is not merely the result of individual cruelty. It is a systemic vulnerability—embedded in relational proximity, ecological stress, and caregiver breakdown. The youngest victims are not only the most fragile; they are also the least able to disclose abuse, the least visible to outsiders, and the most affected by their immediate environments. In this sense, child abuse is not simply a personal failing. It is a structural failure of protection across familial, institutional, and social domains.

To recognize this is not merely to describe a problem. It is to confront a moral imperative. If self-defense rests on the preservation of life and autonomy, then the defense of the child is its most foundational expression. The task is not only to intervene when harm becomes visible, but to cultivate conditions in which the most dependent among us are not subject to hidden violence, structural neglect, or fatal omission.

3.5.2 Environmental Risk and Direct Violence

The landscape of harm to children extends far beyond the walls of the family home. As children grow, their exposure to danger does not vanish—it evolves. What begins in early life as vulnerability to domestic abuse or neglect gradually becomes exposure to a broader ecology of environmental hazard and interpersonal threat. By adolescence, the risk environment increasingly includes public and institutional spaces, where danger is less hidden but no less devastating.

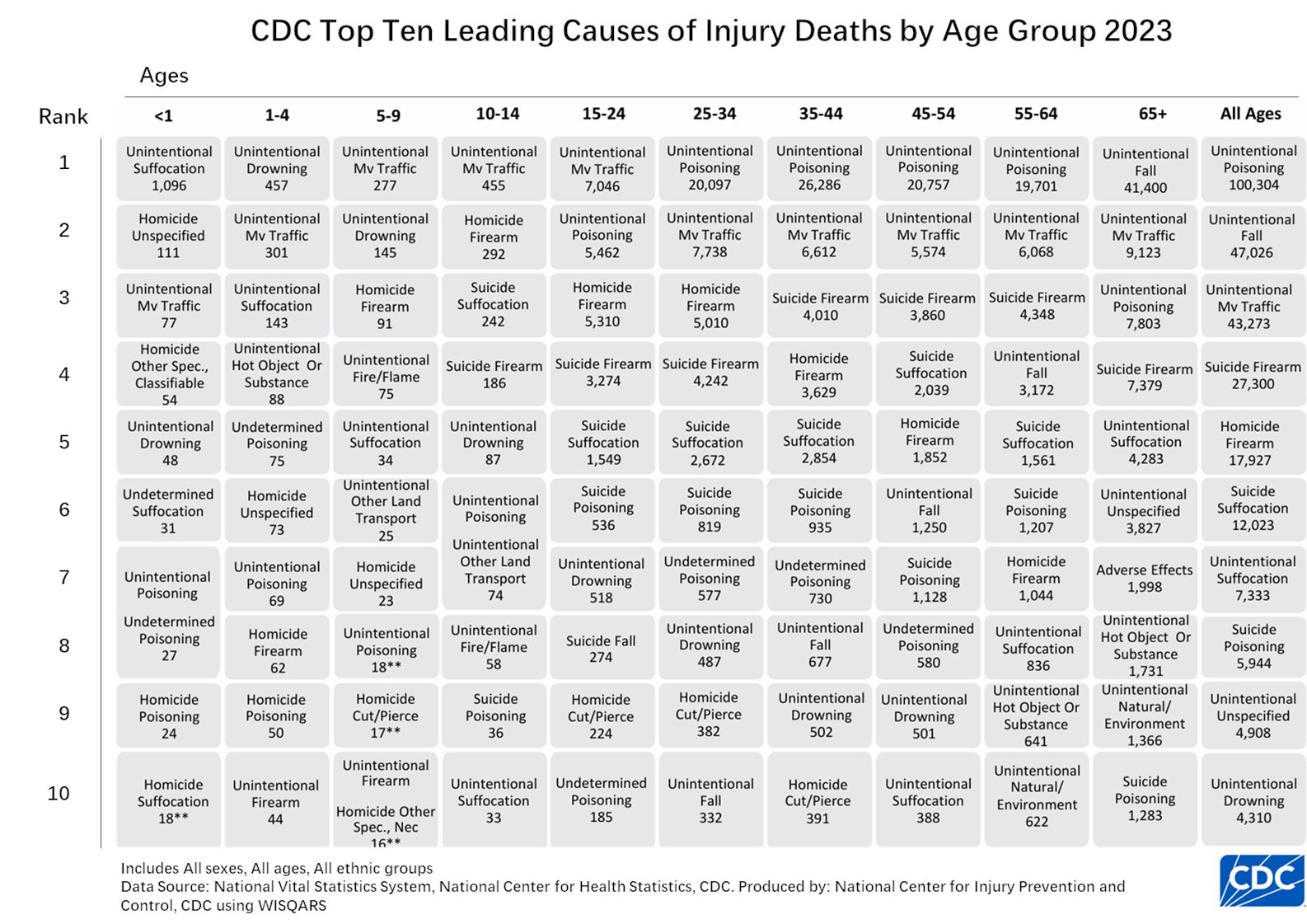

Firearm violence now ranks as the second leading cause of death among American children and teenagers.[clxiv] In a single year, more than 3,400 youth were killed by firearms, with over 18,000 injured.[clxv] For younger children aged one to four, the leading causes of injury-related death include drowning, suffocation, and motor vehicle accidents—preventable harms that speak to persistent gaps in supervision, infrastructure, and environmental safety.[clxvi] But by ages 10 to 14, the landscape changes dramatically: firearm homicide and suicide emerge among the top causes of death.[clxvii] These are not isolated anomalies. They represent a structural shift—where environmental exposure gives way to direct interpersonal and self-directed violence.

This age-patterned trajectory of harm is not accidental. It is shaped by the interaction of developmental vulnerability, relational instability, and broader contextual failure. Children are harmed not only in homes, but in streets, schools, cars, and recreational spaces. Some die from neglect. Others from assault. Still others from preventable accidents that reflect not malice, but systems ill-equipped to protect. In all cases, the result is the same: a life extinguished or altered before it has developed the capacity to defend itself.

Understanding direct violence against children requires that we see it not as separate from maltreatment, but as its external continuation—a widening of the circle of threat. Protecting children therefore means more than intervening in domestic crises. It means attending to the spaces they inhabit, the systems that touch their lives, and the social structures that determine whether risk is identified, ignored, or allowed to escalate. As UNICEF has highlighted, measuring and addressing violence against children requires consistent global frameworks, since definitional gaps and fragmented reporting often conceal the full scope of risk.[clxviii]

3.5.3 Structural Harm and Indirect Violence

Not all harm to children takes the form of immediate assault. Many threats are slow-moving, ambient, and systemic. These forms of violence do not leave visible marks, yet they shape the developmental terrain on which all other risks emerge. Poverty, instability, and chronic deprivation—though not always recognized as legal violations—function as chronically harmful conditions. They shape who is protected, who is overlooked, and who grows up surrounded by risk.[clxix]

Millions of children in the United States lack consistent access to safe housing, adequate nutrition, basic healthcare, and quality education.[clxx] These are not peripheral concerns. They produce predictable patterns of harm—concentrating vulnerability in overburdened communities and compounding the effects of any interpersonal violence that may follow. In such settings, violence does not begin at the moment of impact. It begins in the erosion of security, the absence of care, and the breakdown of relational support.

Educational institutions often exacerbate this problem. Under-resourced schools, overcrowded classrooms, and punitive disciplinary practices create environments of control rather than care. In some districts, exclusionary policies disproportionately target marginalized youth, reinforcing what has been called the school-to-prison pipeline—a pattern in which children are not supported through conflict, but removed and redirected toward justice system involvement.[clxxi] Here, institutional response becomes a source of harm rather than a site of protection.

The ethical gravity of these conditions lies in their invisibility. They rarely implicate a single perpetrator, but their effects are cumulative and enduring. A child raised in an environment where safety is unreliable and basic needs go unmet is not merely “at risk.” They are already being harmed. And those harms persist long after childhood, influencing how individuals interpret danger, manage emotion, and relate to themselves and others.

In the context of self-defense, this demands a wider lens. A defensive posture cannot begin at the moment of attack, nor can it be limited to physical intervention. It must acknowledge that many threats to autonomy, dignity, and well-being are encountered long before a child has the capacity to resist. To defend the child is not merely to intervene in violence—it is to preserve the conditions under which moral agency can take root. The child is not only vulnerable; they are in formation.

Violence against children—whether immediate, ambient, or neglected into silence—is not merely a private tragedy. It is a civic and ethical failure. Any society that claims to value justice must treat the prevention of child harm not as a bureaucratic obligation, but as a core commitment to human flourishing.[clxxii]

4. Living With Risk: Lessons from the Landscape of Violence

The case study presented in this report reveals an uncomfortable but necessary truth: violence is not an aberration. It is a recurring feature of ordinary life. Across the United States, millions of people each year experience harm that is deeply personal, patterned, and frequently preventable. From intimate partner violence and sexual assault to child abuse and firearm deaths, the data portray a persistent ecology of risk—one that falls most heavily on women, children, and those living in conditions of economic hardship, social dislocation, or institutional fragility.

These numbers are not abstractions. They are markers of harm embedded in the fabric of everyday existence. Violence takes many forms—assault, coercion, neglect—and occurs in spaces that should offer safety: the home, the school, the workplace, the street. It may erupt suddenly or accumulate gradually, often intensifying over time. And it is compounded by the social conditions that constrain a person’s ability to anticipate, resist, or recover from threat. Whether born of interpersonal betrayal or systemic failure, the message is the same: harm is not random, nor is it evenly distributed. It follows pathways of vulnerability, opportunity, and constrained choice.

For those seeking to understand or practice self-defense, this reality cannot be ignored. It tells us not only that violence is common, but how and where it most often appears. It warns us of its varied forms—some explosive and immediate, others invisible, corrosive, and sustained. It draws our attention to those most at risk, and to the environments where threat emerges and protection is often absent. Above all, it reminds us that self-defense is not simply a reactive skill—it is a form of awareness: of context, of pattern, of reality.

That reality, as this article has shown, is layered and complex. Not all violence is impulsive; much of it is deliberate. Not all threats are physical; many are relational, psychological, or circumstantial. The deeper insight is that violence is not only an event—it is often a condition. It can fester in silence, reside in relationships, or erupt without warning. A credible approach to self-defense must therefore begin not with physical technique, but with understanding.

But understanding alone is insufficient. To respond to violence responsibly, one must grapple with the moral and legal frameworks that govern defensive action. What constitutes a justified defense? What are the ethical boundaries of force? How do we navigate the space between passivity and excess?

These are the questions that future articles will explore. If this article has mapped the contours of violence—its forms, contexts, and consequences—the next article marks a pivotal shift: from describing what violence is to asking what we are permitted, obligated, or justified to do in response. It examines the biological roots of self-preservation, the ethical status of resistance, and the foundational principles that undergird the right to oppose illegitimate harm.

To defend oneself, as we will argue, is not merely to survive. It is to act as a moral agent in a world that offers no guarantee of safety. It is to affirm—even under threat—the right to live with autonomy, agency, dignity, and responsibility.

About the Author

Nathan A. Wright

Nathan is the Managing Director and Chief Instructor at Northern Sage Kung Fu Academy, and Chief Representative of Luo Guang Yu Seven Star Praying Mantis in Canada and China. With over 25 years of experience living in China, he is deeply committed to passing on traditional martial arts in its most sincere form. As part of his passion Nathan regularly writes on related topics of self-defense, combat, health, philosophy, ethics, personal cultivation, and leadership.

Endnotes

[i] World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. Edited by Etienne G. Krug, Linda L. Dahlberg, James A. Mercy, Anthony B. Zwi, and Rafael Lozano. Geneva: WHO, 2002, 30.

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-violence-and-health.

[ii] World Health Organization. Violence: A Public Health Priority. Geneva: WHO, 1996. WHO/EHA/SPI.POA.2.

[iii] Moore, Mark H. “Public Health and Criminal Justice Approaches to Prevention.” In Understanding and Preventing Violence: Volume 4, Consequences and Control, edited by Jeffrey A. Roth and Albert J. Reiss Jr., 1–20. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1995, 3-6.

[iv] Rutherford, Andrew. “Violence: A Brief Cultural and Conceptual History.” In The Oxford Handbook of Criminology, edited by Mike Maguire, Rod Morgan, and Robert Reiner, 2–23. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

[v] World Health Organization. “Violence Prevention Alliance: Definition and Typology of Violence.” WHO, 2024. https://www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/definition/en

[vi] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 30.

[vii] Walters, Richard H., and Ross D. Parke. “Social Motivation, Dependency, and Susceptibility to Social Influence.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 1, edited by Leonard Berkowitz, 231–276. New York: Academic Press, 1964.

[viii] Anderson, Craig A., and Brad J. Bushman. “Human Aggression.” Annual Review of Psychology 53 (2002): 27–51.

[ix] Stark, Evan. Coercive Control: How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

[x] World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002, 30.

[xi] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence.” Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2019.

[xii] Moore, “Public Health and Criminal Justice Approaches,” 6-7.

[xiii] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention.” Last modified 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect

[xiv] Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, s.34. Government of Canada.

[xv] R v Khill, 2021 SCC 37, [2021] 2 SCR 237

[xvi] Garner, Bryan A., ed. Black’s Law Dictionary. 11th ed. St. Paul, MN: Thomson Reuters, 2019.

[xvii] World Health Organization. “Elder Abuse.” Fact Sheet, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/elder-abuse.

[xviii] Galtung, Johan. “Cultural Violence.” Journal of Peace Research 27, no. 3 (1990): 291–305.

[xix] Farmer, Paul. “An Anthropology of Structural Violence.” Current Anthropology 45, no. 3 (2004): 305–325.

[xx] World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: WHO, 2002.

[xxi] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31.

[xxii] Leemis, Rachel W., et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2016/2017 Report on Intimate Partner Violence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022, 2. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs/NISVSReportonIPV_2022.pdf.

[xxiii] World Health Organization. Violence Against Women: Key Facts. Geneva: WHO, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

[xxiv] Marc Riedel and Wayne N. Welsh, Criminal Violence: Patterns, Causes, and Prevention, 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 171-173,195-199.

[xxv] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth Violence Prevention. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2023.

[xxvi] UNESCO. Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying. Paris: UNESCO, 2019.

[xxvii] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Workplace Violence Prevention. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2021.

[xxviii] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31.

[xxix] Riedel and Welsh, Criminal Violence, 199.

[xxx] World Health Organization. Sexual Violence: Key Facts. Geneva: WHO, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

[xxxi] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Preventing Sexual Violence. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence

[xxxii] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Global Report on Trafficking in Persons. Vienna: UNODC, 2020.

[xxxiii] World Health Organization. INSPIRE: Seven Strategies for Ending Violence Against Children. Geneva: WHO, 2016.

[xxxiv] Smith, Carly Parnitzke, and Jennifer J. Freyd. “Institutional Betrayal.” American Psychologist 69, no. 6 (2014): 575–587.

[xxxv] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31.

[xxxvi] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Community Violence Prevention. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/community-violence

[xxxvii] Finkelhor, David, and Heather Turner. “Poly-Victimization in Children and Youth.” Child Abuse & Neglect 34, no. 4 (2010): 247–259

[xxxviii] Finkelhor, David, Richard Ormrod, Heather Turner, and Sherry L. Hamby. “Poly victimization: Children’s Exposure to Multiple Types of Violence, Crime, and Abuse.” OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2011.

[xxxix] Riedel and Welsh, Criminal Violence, 128.

[xl] U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Hate Crime Statistics, 2023. Washington, DC: DOJ, 2023.

[xli] American Psychological Association (APA). The Psychology of Hate Crimes. Washington, DC: APA, 2019.

[xlii] World Health Organization. INSPIRE: Seven Strategies for Ending Violence Against Children. Geneva: WHO, 2016.

[xliii] World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. Edited by Etienne G. Krug, Linda L. Dahlberg, James A. Mercy, Anthony B. Zwi, and Rafael Lozano. Geneva: WHO, 2002.

[xliv] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31.

[xlv] World Health Organization. Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: WHO, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643

[xlvi] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Suicide Prevention: Fast Facts. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts

[xlvii] American Psychological Association (APA). Suicide and Trauma. Washington, DC: APA, 2019.

[xlviii] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31.

[xlix] World Health Organization. “Violence Prevention Alliance: Definition and Typology of Violence.” WHO, 2024. https://www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/definition

[l] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31.

[li] Riedel and Welsh, Criminal Violence, 147.

[lii] World Health Organization. Violence Against Women: Key Facts. Geneva: WHO, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

[liii] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Preventing Intimate Partner Violence. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence

[liv] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31.

[lv] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Community Violence Prevention. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/community-violence

[lvi] Finkelhor, David, and Heather Turner. “Poly-Victimization in Children and Youth.” Child Abuse & Neglect 34, no. 4 (2010): 247–259.

[lvii] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31.

[lviii] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2022. Geneva: UNHCR, 2023. https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2022

[lix] Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP). UCDP Conflict Data Set. Uppsala University, 2023. https://ucdp.uu.se

[lx] World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: WHO, 2002.

[lxi] Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, s.34. Government of Canada.

[lxii] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31

[lxiii] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31.

[lxiv] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Injury Prevention and Violence. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/injury

[lxv] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2019.

[lxvi] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31.

[lxvii] Riedel and Welsh, Criminal Violence, 106-107.

[lxviii] World Health Organization. Violence Against Women: Key Facts. Geneva: WHO, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

[lxix] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Preventing Sexual Violence. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence

[lxx] R. W. Leemis, N. Friar, S. Khatiwada, M. S. Chen, M. Kresnow, S. G. Smith, S. Caslin, and K. C. Basile, The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2016/2017 Report on Intimate Partner Violence (Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC, 2022), 2, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs/NISVSReportonIPV_2022.pdf

[lxxi] Connie Mitchell and Deirdre Anglin, eds., Intimate Partner Violence: A Health-Based Perspective (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

[lxxii] Campbell, Rebecca, Emily Dworkin, and Giannina Cabral. “An Ecological Model of the Impact of Sexual Assault on Women’s Mental Health.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 10, no. 3 (2009): 225–246.

[lxxiii] WHO, World Report on Violence and Health, 31.

[lxxiv] Stark, Evan. Coercive Control: How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

[lxxv] American Psychological Association (APA). Violence and Abuse: Mental Health Consequences. Washington, DC: APA, 2019.

[lxxvi] World Health Organization. Child Maltreatment: Key Facts. Geneva: WHO, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment

[lxxvii] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau, Child Maltreatment 2023 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, January 8, 2025), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/report/child-maltreatment-2023

[lxxviii] World Health Organization. Child Maltreatment: Key Facts. Geneva: WHO, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment

[lxxix] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau, Child Maltreatment 2023 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, January 8, 2025),

[lxxx] World Health Organization. Elder Abuse: Key Facts. Geneva: WHO, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/elder-abuse

[lxxxi] World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. Edited by Etienne G. Krug, Linda L. Dahlberg, James A. Mercy, Anthony B. Zwi, and Rafael Lozano. Geneva: WHO, 2002.

[lxxxii] Anderson, Craig A., and Brad J. Bushman. “Human Aggression.” Annual Review of Psychology 53 (2002): 27–51.

[lxxxiii] Burton, John W. Conflict: Human Needs Theory. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

[lxxxiv] Galtung, Johan. “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research.” Journal of Peace Research 6, no. 3 (1969): 167–191.

[lxxxv] Dean G. Pruitt, “Escalation and De-escalation,” in The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice, 3rd ed., ed. Morton Deutsch, Peter T. Coleman, and Eric C. Marcus (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2014), 107–110.

[lxxxvi] American Psychological Association. APA Dictionary of Psychology. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: APA, 2015.

[lxxxvii] Cuevas, Carlos A., and Callie Marie Rennison, eds. The Wiley Handbook on the Psychology of Violence. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2016.

[lxxxviii] Jane L. Ireland, Philip Birch, and Carol A. Ireland, eds., The Routledge International Handbook of Human Aggression: Current Issues and Perspectives (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2018).

[lxxxix] Dodge, Kenneth A., and John D. Coie. “Social-Information-Processing Factors in Reactive and Proactive Aggression in Children’s Peer Groups.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53, no. 6 (1987): 1146–1158.

[xc] Baron, Robert A., and Deborah R. Richardson. Human Aggression. 2nd ed. New York: Plenum Press, 1994.

[xci] Monahan, John. The Clinical Prediction of Violent Behavior. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1981.

[xcii] Garner, Bryan A., ed. Black’s Law Dictionary. 11th ed. St. Paul, MN: Thomson Reuters, 2019, 788–789.

[xciii] Johnson v. United States, 559 U.S. 133 (2010), 140.

[xciv] Revised Code of Washington, RCW 10.120.010. Definitions (Olympia, WA: Washington State Legislature).

[xcv] Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, s. 34 (Ottawa: Government of Canada).

[xcvi] Alpert, Geoffrey P., and Roger G. Dunham. Understanding Police Use of Force: Officers, Suspects, and Reciprocity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, 3–6.

[xcvii] Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, s. 34. Government of Canada.

[xcviii] Dodge, Kenneth A., and John D. Coie. “Social-Information-Processing Factors in Reactive and Proactive Aggression in Children’s Peer Groups.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53, no. 6 (1987): 1146–1150.

[xcix] Berkowitz, Leonard. Aggression: Its Causes, Consequences, and Control. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1993, 57–61.

[c] Raine, Adrian, Paul H. Brennan, Sarah Farrington, and David P. Farrington. “Reactive, Proactive, and Psychopathic Aggression in Children and Adolescents: A Review and Meta-analysis.” Behavioral Sciences & the Law 24, no. 6 (2006): 816–819.

[ci] Vitaro, Frank, Mara Brendgen, and Richard E. Tremblay. “Proactive and Reactive Aggression: A Developmental Perspective.” Development and Psychopathology 14, no. 1 (2002): 131–135.

[cii] World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. Edited by Etienne G. Krug, Linda L. Dahlberg, James A. Mercy, Anthony B. Zwi, and Rafael Lozano. Geneva: WHO, 2002, 5–7.

[ciii] Riedel, M., & Welsh, W. N. (2011). Criminal violence: Patterns, causes, and prevention (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

[civ] Ángel Romero-Martínez, Carolina Sarrate-Costa, and Luis Moya-Albiol, “Reactive vs. Proactive Aggression: A Differential Psychobiological Profile? Conclusions Derived from a Systematic Review,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 136, no. 4 (March 2022): [page or article number], https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104626

[cv] World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. Edited by Etienne G. Krug, Linda L. Dahlberg, James A. Mercy, Anthony B. Zwi, and Rafael Lozano. Geneva: WHO, 2002, 5–7.

[cvi] Riedel, M., & Welsh, W. N. (2011). Criminal violence: Patterns, causes, and prevention (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

[cvii] World Health Organization. Child Maltreatment: Key Facts. Geneva: WHO, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment

[cviii] Smith, Carly Parnitzke, and Jennifer J. Freyd. “Institutional Betrayal.” American Psychologist 69, no. 6 (2014): 576–580.

[cix] Galtung, Johan. “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research.” Journal of Peace Research 6, no. 3 (1969): 167–191, at 171–174.

[cx] Farmer, Paul. “An Anthropology of Structural Violence.” Current Anthropology 45, no. 3 (2004): 305–325, at 307–310.

[cxi] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Global Study on Homicide 2019. Vienna: UNODC, 2019, 29–33.

[cxii] Galtung, Johan. “Cultural Violence.” Journal of Peace Research 27, no. 3 (1990): 291–305, at 291–295.

[cxiii] World Health Organization. Violence Against Women: Key Facts. Geneva: WHO, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

[cxiv] World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. Edited by Etienne G. Krug, Linda L. Dahlberg, James A. Mercy, Anthony B. Zwi, and Rafael Lozano. Geneva: WHO, 2002, 5–7.

[cxv] Cuevas, Carlos A., and Callie Marie Rennison, eds. The Wiley Handbook on the Psychology of Violence. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2016.

[cxvi] Tapp, Susannah N., and Emilie J. Coen. Criminal Victimization, 2023. NCJ 307184. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2024. https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/cv23.pdf.

[cxvii] Truman, Jennifer L., and Lynn Langton. Criminal Victimization, 2014. NCJ 248973. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2015. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv14.pdf.

[cxviii] Morgan, Rachel E., and Jennifer L. Truman. Criminal Victimization, 2019. NCJ 255113. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2020. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv19.pdf

[cxix] Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, 3; Rachel E. Morgan and Alexandra Thompson, Criminal Victimization, 2020, NCJ 301775 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2021), 2.

[cxx] Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, tables 1–2.

[cxxi] Federal Bureau of Investigation, Crime Data Explorer: Supplementary Homicide Report (SHR) (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.); National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics Report 68 (6) (Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019)

[cxxii] Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, table 6.

[cxxiii] Thompson, Alexandra, and Susannah N. Tapp. Criminal Victimization, 2022. NCJ 306620. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2023. https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/cv22.pdf.

[cxxiv] Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, tables 7–8.

[cxxv] Federal Bureau of Investigation, Property Crime: Crime in the United States, 2019 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2020).

[cxxvi] Morgan and Truman, Criminal Victimization, 2019, table 1.

[cxxvii] Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, table 1.

[cxxviii] Morgan, Rachel E., and Alexandra Thompson. Criminal Victimization, 2020. NCJ 301775. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2021. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv20.pdf.

[cxxix] Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, table 9.

[cxxx] Thompson and Tapp, Criminal Victimization, 2022, 7–8; Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, table 6.

[cxxxi] Federal Bureau of Investigation, Crime in the United States, 2019: Table 1 – Crime in the United States by Volume and Rate per 100,000 Inhabitants, 1999–2019 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2020)

[cxxxii] Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, table 7.

[cxxxiii][cxxxiii] Thompson and Tapp, Criminal Victimization, 2021, table 1.

[cxxxiv] Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, table 1.

[cxxxv] Thompson and Tapp, Criminal Victimization, 2021, 3.

[cxxxvi] Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, 3.

[cxxxvii] Thompson and Tapp, Criminal Victimization, 2021, table 7; Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, table 7.

[cxxxviii] Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, table 6.

[cxxxix] Susannah N. Tapp and Emilie J. Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, NCJ 307184 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2024), 6–7, table 7.

[cxl] Ibid., 8, table 9.

[cxli] Ibid., 5, table 2.

[cxlii] Alexandra Thompson and Susannah N. Tapp, Criminal Victimization, 2022, NCJ 306620 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2023), 4, table 2.

[cxliii] Aggregated totals from Rachel E. Morgan and Jennifer L. Truman, Criminal Victimization, 2019, NCJ 255113 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2020), 2–3, table 1; Rachel E. Morgan and Alexandra Thompson, Criminal Victimization, 2020, NCJ 301775 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2021), 3, table 1; Alexandra Thompson and Susannah N. Tapp, Criminal Victimization, 2021, NCJ 305101 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2022), 2–3, table 1; Thompson and Tapp, Criminal Victimization, 2022, 4, table 1; and Tapp and Coen, Criminal Victimization, 2023, 5, table 1.

[cxliv] Rachel W. Leemis, Nimesh Patel Friar, Sharon G. Smith, Kathleen C. Basile, and Matthew J. Breiding, The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2016/2017 Report on Intimate Partner Violence (Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022), 9–11, table 1.

[cxlv] Ibid., 14–15, table 2.

[cxlvi] Ibid., 18–19, table 3.

[cxlvii] Ibid., 22, table 4.

[cxlviii] Ibid., 26–28, table 5.

[cxlix] Ibid., 32–34, table 6.

[cl] Jennifer L. Truman and Lynn Langton, Criminal Victimization, 2014, NCJ 248973 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, 2015), 8; Leemis et al., NISVS 2016/17, 40.

[cli] World Health Organization, Violence Against Women: Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Against Women (Geneva: World Health Organization, March 2021), https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women.

[clii] Jacquelyn C. Campbell, “Health Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence,” The Lancet 359, no. 9314 (2002): 1331–1336.

[cliii] Jacqueline M. Golding, “Intimate Partner Violence as a Risk Factor for Mental Disorders: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Family Violence 14, no. 2 (1999): 99–132; Michele C. Black, Kathleen C. Basile, Matthew J. Breiding, et al., The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report (Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011), 37–42.